SVG Storyboard Export Templates¶

Krita’s Görsel Taslak Paneli has a variety of options for exporting your storyboards to PDF or SVG file formats.

The simplest of those are the procedural layout options, such as “rows”, “columns”, and “grid” modes. Using these modes, Krita can generate a somewhat basic page layout with just a few settings. As a quick and easy preview or in a pinch, these modes do a decent job of showing you what you need to see.

However, for the highest level of control and the best aesthetics, the layout option that we recommend is one that makes use of an SVG template file. This template file, either written by hand or made in an SVG editor program like Inkscape, gives you full control over where and how your storyboard elements are to be placed on the final exported page, with full support for background and overlay layers.

Using an SVG template, you can hopefully export storyboards that fit the needs of whatever project you’re working on, or even fit the exact specifications of an existing storyboard paper format!

Krita’s Default SVG Storyboard Export Template¶

For convenience, Krita ships with its own default SVG storyboard template that you’re (of course) free to use for any project, to modify to suit your needs, and to study from when creating your own SVG template files. (And, not to toot my own horn or anything but I’d say it looks pretty cool, too!)

So, if you’re simply looking for an awesome way to export and present the storyboards that you’ve made in Krita, you can stop reading now and just use the SVG template file that comes with Krita’s default resources.

If you still want or need to create your own SVG storyboard export template file, however, read on!

Vector Editing with Inkscape¶

While it’s perfectly possible to write one of these SVG template files by hand (if you’re a masochist), the way that I recommend is to use an SVG editor like Inkscape. Much like Krita, Inkscape is a free and open source program that you can use to create vector art, design logos, and more. In our case, we’re going to use it to create a template file that Krita can understand and work with. Inkscape is pretty good, so give it a try! https://inkscape.org/

This is not going to be a full Inkscape tutorial or anything (I couldn’t give one if I wanted to, frankly), but this page should hopefully give you the essential details needed to create a working storyboard export template.

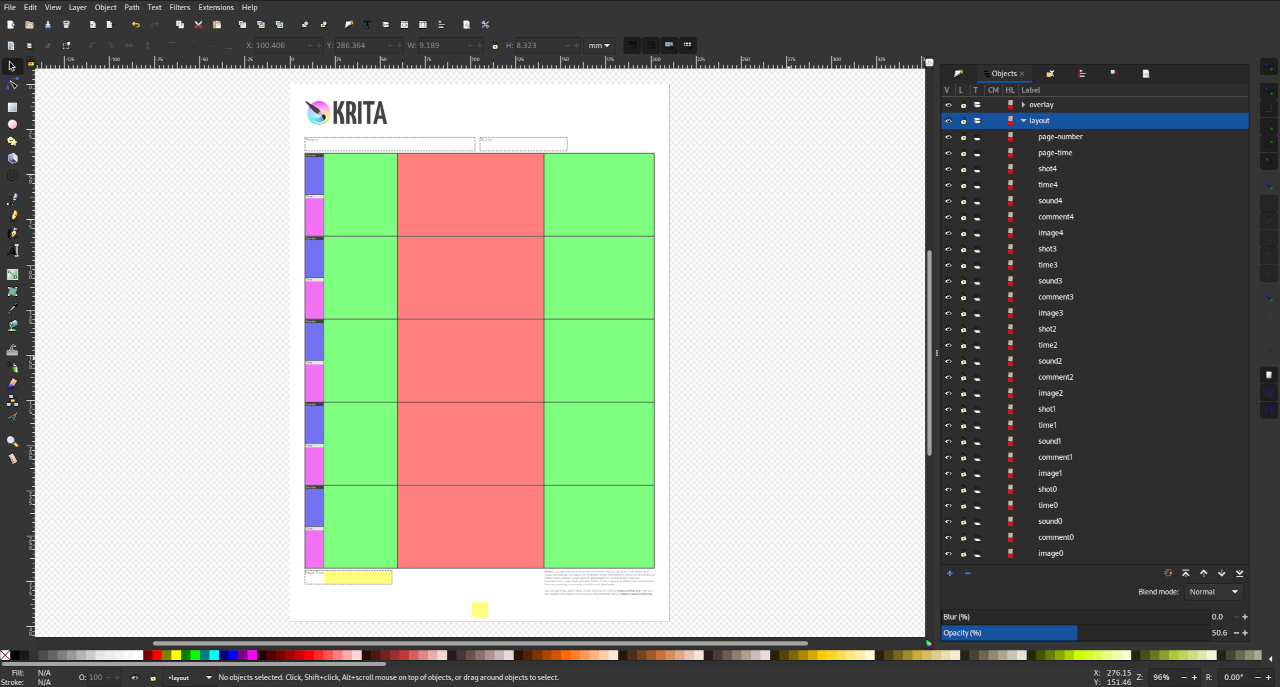

Krita’s default storyboard export template loaded into Inkscape. Labeled boxes are used to control the layout of elements. (Pretty colors are optional.)¶

Designing Your Own SVG Storyboard Export Template¶

Setup:¶

After opening Inkscape, the first thing we need to do is select our preferred Page Size and Display Unit. Both of these settings can be found in the “File > Document Properties…” menu inside of Inkscape. I decided to go with A4 paper and mm units, but whatever you want should also work.

Next, we need to create a few specific layers (background, layout, and overlay) that Krita will recognize and use to draw our page correctly. The “background” and “overlay” layers are relatively simple: anything that belongs to the “background” layer will be drawn underneath the storyboard elements (the images, comments and other metadata), and anything that belongs to the “overlay” layer will be drawn on top of the storyboard elements. Whether you should use these layers in your own storyboard export template depends on your own needs and how you design your sheet. Finally, the “layout” layer is where we will be placing the various rectangles that we will use to tell Krita exactly where we want our storyboard elements to appear. We’ll run through that process in detail later, but first we need to get the layers set up correctly.

As of the time of writing this, Inkscape makes it slightly complicated to change the ID of our layers. First we need to open Inkscape’s Object > Objects… panel, where we can see all of our layers, groups, and other SVG objects. Click on the + and create a layer called “background”, then again with the name “layout”, and finally another one called “overlay”.

This next part is important! You should have 3 layers now, but because we use the ID attribute of the SVG object, we have to do a little bit more work to make sure that Krita will recognize our layers. If you select your layer and open Inkscape’s Object > Object Properties… panel, you will see that everything is grayed out and we are not able to change the “ID” parameter! Here’s how to get around that: first, we have to convert our layers into groups by clicking on the icon in the T column on Inkscape’s Objects… panel. Once all three of our layers are groups, we can open the Object Properties… panel and edit the “ID” parameter. The ID of each layer should be “background”, “layout”, and “overlay” respectively.

Uyarı

Another weird thing is that, right now, Inkscape requires you to hit Enter or click on the Set button after changing the ID, so make sure that you hit enter or click set!

Once you’ve made sure that each of your groups has been given the appropriate ID, the last thing that you need to do is convert your groups back into layers the same way that we did it before, by clicking on the icon in the T column.

Tüyo

Ok, that was a bit more complicated that we wanted it to be, but it’s all downhill from here! If you run into problems creating your template, it’s probably going to be some part of that last step that’s to blame, so it’s worth double-checking that each of your layers has the correct ID. (By the way, the ID can also be edited manually using a text editor, but that’s probably out of the scope of this tutorial.)

Whew… Ok. So now the [slightly] more fun stuff…

Background and Overlay Visuals:¶

At this point you have the option of adding whatever visual design elements you want to the “background” and “overlay” layers. If you have an actual piece of storyboard paper that you want to use then I recommend putting it into the “background” layer, and if you want to overlay some panels or text, I recommend adding them to the “overlay” layer. Just remember, everything in the “background” layer will be rendered under your storyboard elements, and everything in the “overlay” layer will be rendered on top.

Not

As of Inkscape 1.1, new objects are automatically added to the layer that you currently have selected or that you last added something to. As such, I find it easiest to work on one layer at a time.

Uyarı

Also as of Inkscape 1.1, I find that text often gets transformed in strange ways that make it appear correctly in Inkscape but show up in the completely wrong place in Krita and other programs! I don’t know why this happens or how to fix it, but I do know how to work around it. If you use text elements and you run into problems with them not showing up where they’re supposed to, I recommend converting them to paths with the Path > Object to Path function.

Layout Basics:¶

Once we have our page looking the way we want it to, we’re ready to populate the “layout” layer.

Krita will use the rectangles that you place into this layer to determine where to put various storyboard elements, including images, comments, and metadata. As an example, Krita will find all of the rectangles that have labels beginning with the word “image” (image0, image1, image2, etc.) and replace them with your storyboard images. Cool, huh?

Tüyo

For organizational reasons I like to color code each rectangle by type (for example making all of the images red, while making the comments green), but because nothing in this layer is ever drawn it makes no visual difference. The rectangles in this layer are used strictly for placement, and they will be replaced with the contents of your storyboards!

It doesn’t really matter how you arrive at the final result, but I think a good way of doing this quickly is to place rectangles for the various elements of a single storyboard first, select them all and create duplicates for as many boards that you want to fit on your page. For Krita’s default storyboard export template, we decided that it would be nice to have 5 storyboards with 2 comment tracks per page. It’s up to you how you want to layout your storyboard pages.

So let’s layout a storyboard…

Uyarı

Don’t forget to save!

Creating Your Layout (Part 1):¶

The first thing I would start with is the image rectangle. With the “layout” layer selected in Inkscape, drag a rectangle wherever you want the first storyboard image to be placed. To tell Krita that we want to replace this rectangle with this page’s first storyboard image, all we have to do is rename this rectangle to something like “image0” or “image1” (the number doesn’t matter as much as the order).

Tüyo

Once you’ve renamed your rectangle you can open Inkscape’s Object Properties… panel to see that its “label” attribute has changed. This “label” attribute is what Krita looks for when placing elements, so it’s really important! If something is showing up in the wrong place, you’ve probably just forgotten to change the label (…or click on the “set” button).

Now we do the same thing for comments. As the template maker, it’s up to you to decide how many comment tracks you want to support and what those tracks should be used for and named. Like I mentioned above, I opted for 2 comment tracks on the default template. One, simply called “comment”, can be used for whatever you want, but probably for a short description of the action in each shot, and should match the default name of a comment track within Krita. The other one, called “sound”, is meant to be used as a description of the audio during each cut, including dialogue, sound effects, and background music. Having studied some of the storyboard books that I own from shows that I love, I decided to put “sound” on the left side of the image, and “comment” on the right.

Not

Because we wanted to support any number of comment tracks with any name, the user has to make sure that the names of their comment tracks within Krita’s Görsel Taslak Paneli match the labels of the rectangles in the SVG storyboard export template that they’re using. For instance, if you’re using Krita’s default storyboard export template file, then you should name your comment tracks “comment” (the default name, by the way) and “sound”, respectively. Similarly, whatever you decide to name the comment rectangles in your template, your users will have to follow the same naming scheme inside Krita. This is important!

The last few layout rectangles we should add before we move on are for metadata. A rectangle named “shot” will be replaced with a unique storyboard shot number, and a rectangle named “time” will be replaced by the duration of the shot, expressed in “Seconds + Frames” format. Of course, just like the “image” and “comment” boxes, these “shot” and “time” boxes will be duplicated later for each of the storyboards that we want on our page. From there we only have “page-number” and “page-time” rectangles left. We probably only need one of these per page, since “page-time” represents the total duration of all of the shots on that page and “page-number” is, well… the page number.

Creating Your Layout (Part 2):¶

OK! At this point we should have enough rectangles in place for a single storyboard shot, including an “image” box, probably one or more “comment” boxes, a “shot” box, a “time” box, as well as the page-specific “page-number” and “page-time” boxes. We’re almost finished!

All we have to do now is decide how many boards we want on our page, duplicate the initial board-specific layout a few times, and then give each of the objects their final, numbered names.

Please go ahead and duplicate your “image”, comment(s), “shot”, and “time” boxes until you’ve filled up your page.

Tüyo

Inkscape’s guides and powerful snapping features make arranging all of your storyboard elements a snap!

Once you’re ready, we just need to make sure that every rectangle has a unique label that ends in a number. Like I mentioned above, these labels, and the numbers hanging off the end, will tell Krita exactly which image, comment, shot number, etc., to place where.

Starting with the “image” boxes, let’s number them from one end to the next, like “image0”, “image1”, “image2”, and so on. For the default template, I created 5 storyboards, and each one has an “image” box with logical numbering from top to bottom. Do the same thing with your “shot” boxes (“shot0”, “shot1”, etc.) and then again with your “time” boxes (“time0”, “time1”, etc.).

Finally, we need to do the comments using the same method. The big difference being that it’s up to you how many comment tracks you have and what they’re called. Just remember, whatever you call them has to match up with the names that the storyboard artist uses for their tracks within Krita’s Storyboard Docker! I went with the default name “comment” (“comment0”, “comment1”, etc.), as well as “sound” (“sound0”, “sound1”, etc.).

After that whole process, every one of the rectangles in your “layout” layer should have a unique and logical name.

And we’re done! Save your storyboard export template as an SVG file, use it to export some storyboards, and feast your eyes on your beautiful, customized storyboard pages.

Not

This is a complicated but reasonably flexible system. Of course, as Krita is an open source and community-driven project, get in touch with the development team if you have ideas (or, even better, a patch!) for how we can improve or build upon this system.